September 2025

Making Progress: An Update on State Land Law Recognition of Indigenous and Local Community Land Rights in Africa

By Liz Alden Wily, PhD

Independent Land Tenure Specialist & LandMark Steering Group Member

Contact: lizaldenwily [at] gmail.com

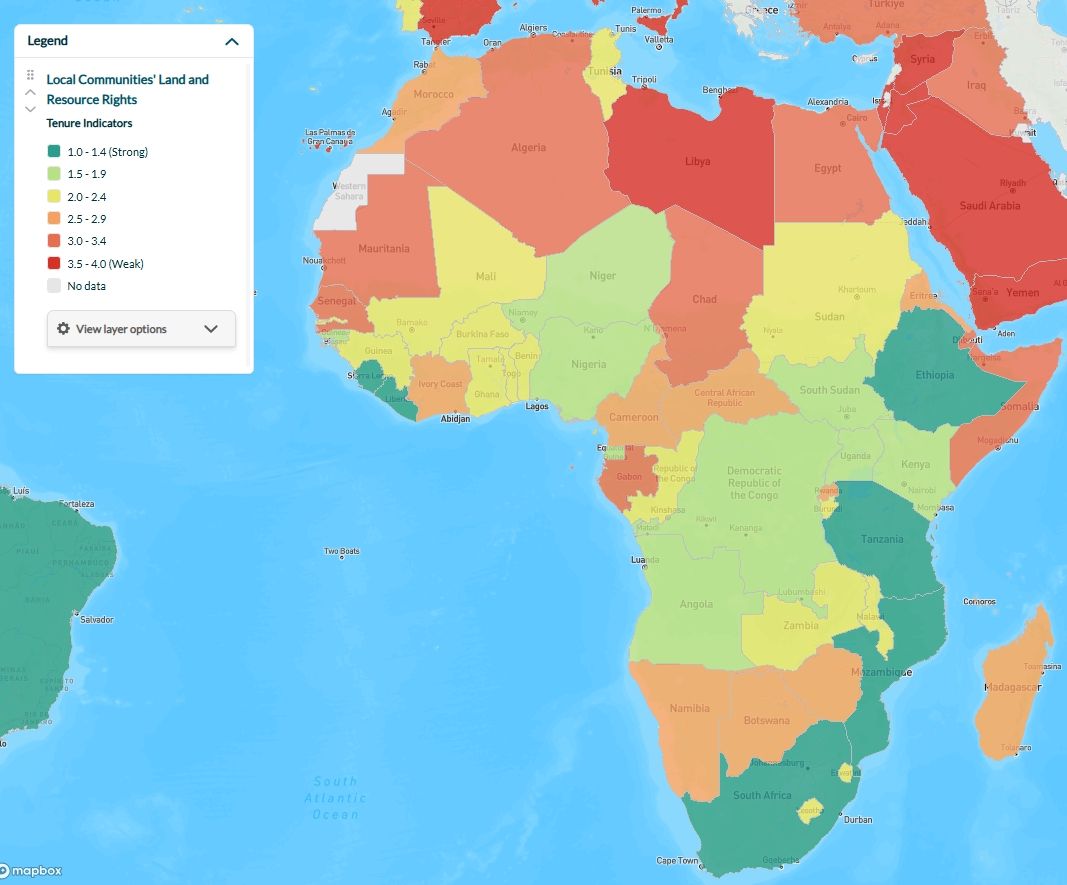

We are pleased to announce that the Indicators of Tenure Security in National Law for 53 of 55 countries in Africa have been updated as of 2025 and are now available to view on LandMark.

Around the world, Indigenous Peoples, Afro-Descendants and local communities seek recognition in state law as legal owners of their customary lands. These customary lands include their family homes and farms as well as the forests, rangelands, or other communal natural resources on which they depend. Government recognition ensures that communities are better equipped to protect their customary lands and resources from outsider encroachment and degradation.

Since 2015, LandMark has assessed the extent to which national laws in various countries recognize the land rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. More information about the dataset can be found here.

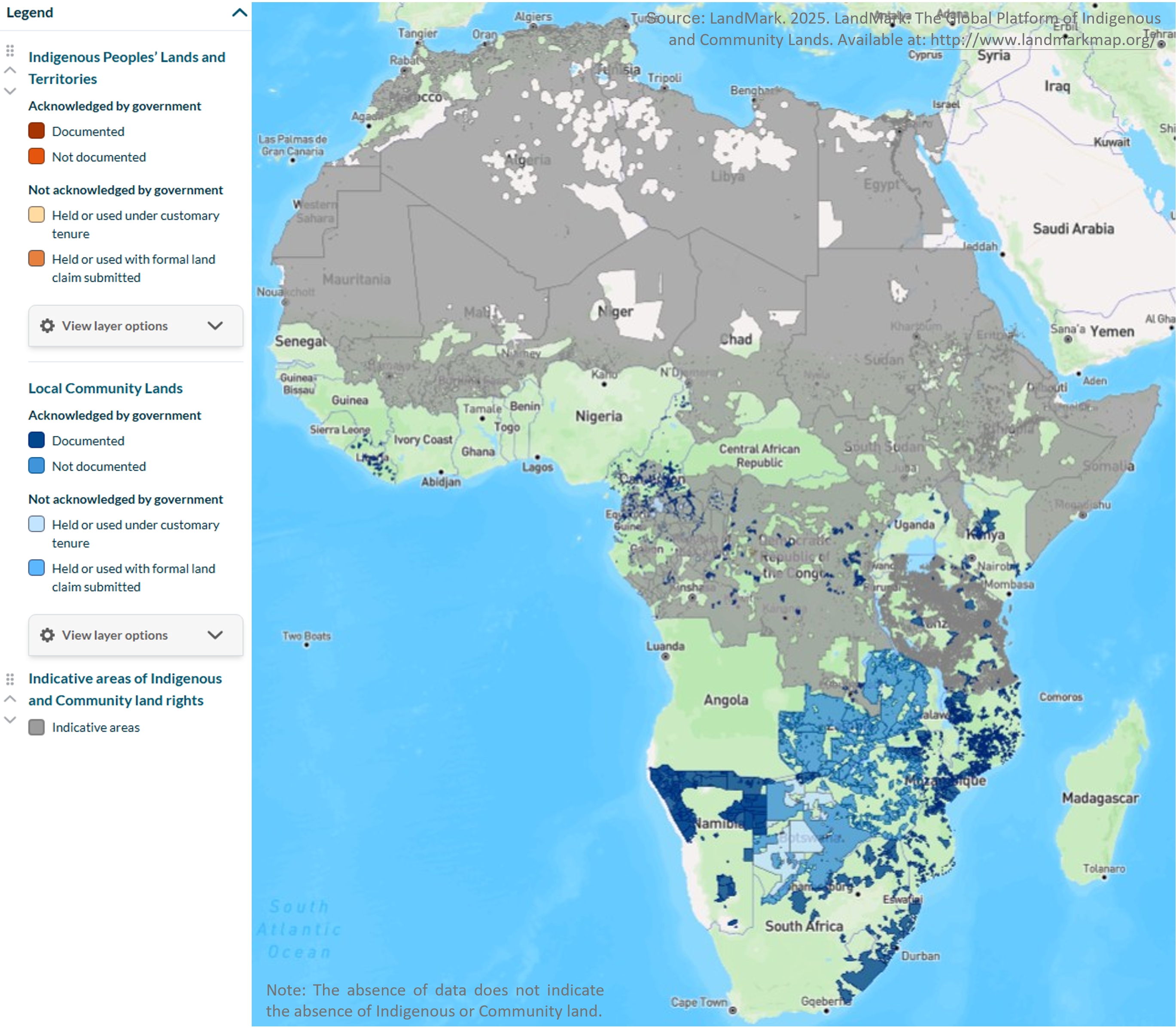

Though there are still gaps, the map below illustrates the vast expanse of the customary community land estate in Africa. At least 725 million people (approx. 80% of Africa’s rural population) depend upon the community-based allocation and use regulation regime of customary tenure. Legal recognition of community ownership, not least to anchor community conservation rules, is emerging as a vital mission for climate change mitigation in its own right. This is because at least three quarters of the customary land estate comprises rangelands, forest, woodlands, wetlands, and other communal assets critical to livelihood, identity, and culture.

A Snapshot of Ten Trends in Community Land Rights Across Africa

The review of the land and natural resource laws in 53 of 55 African countries revealed ten key trends:

1. Land law reforms affecting community lands continues vibrantly in Africa. Since reformism began in 1990, 44 of 53 countries (83%) reviewed in this study have enacted new land laws. Nineteen laws are new since 2015. Several others have committed to enact new land laws (e.g., Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo). Many new laws reflect stronger and more innovative content about community land tenure, including adopting best practices from the laws of other countries–such as stating that customary ownership, while distinct from state-introduced private tenure, has equivalent force and effect in law.

2. While no land law is yet perfect for the customary land sector, 15 countries’ laws (28%) stand out as most supportive overall. The countries with most supportive laws (based on average scores of 10 indicators applied) are Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. Most laws include commons as recognized community property, accept the community as a legal person along with individuals and families, and support community land governance including the right to uphold customary rules. Laws in another 17 countries (32%) adopt ‘mainly positive’ laws, with some countries limiting formal recognition to house and farm plots, and others treating customary certificates only as a stepping stone to issue of state governed titles. Nine other countries (17%) adopt ‘some positive’ laws, which have at least one strength; for example, the new forest regulation in Central African Republic enabling Indigenous Peoples to secure exclusive rights to allocated forests. Finally, 12 countries score poorly (23%) for lack of significant support to customary land holders, or they still lack national land laws, or they have abolished customary tenure with inadequate security of community lands in the new systems.

3. The weakest legal aspect of reforms concerns the legal treatment of off-farm commons as customarily belonging to African communities (Indicator 1: Does the law recognize all rights that Indigenous Peoples or communities exercise over their lands as lawful forms of ownership?).Only 24 of 53 states (45%) recognize commons as lawfully owned, and 12 of these countries have at least one significant limitation (e.g., exclusion of forests from community lands in Angola). The colonial legacy of unfarmed commons as ‘wastelands’ in laws enabling easy taking and reallocation by governments is proving tenacious, especially as the exploitable values of these lands continues to rise.

4. Community land title has evolved as the flagship property construct in Africa, adopted in strongest form in 12 countries (Indicator 3: Does the law require the government to provide indigenous Peoples or communities with a formal title and map to their land?). The countries with strongest scores for Indicator 3 include Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Ethiopia. Since reforms began in the 1990s, provision for formalization has become more and more important to double-lock their rights. Africa has also led in recognizing communities as natural persons, enabling title to be vested directly in the community, removing need to create a legal entity to own the land on its behalf, or for this to remain in government.

5. Recognition of customary tenure as both a land rights regime and a land governance regime are receiving uneven attention in new land laws (Indicator 5: Does the law recognize Indigenous Peoples or the community as the legal authority over the land?).Thirteen national land laws stand out as practical and progressive in requiring communities to elect community land bodies to administer lands and ensure rules are upheld, while also making these bodies accountable to required periodic assemblies of all adults. Elsewhere, community land bodies--even if required--may end up as less autonomous decision-makers than empowered commune or district committees. Reluctance to interfere with a community’s assumed loyalty to its traditional authorities is also seen to result in half measures as to chiefs’ roles, in some cases, failing to sufficiently address rent-seeking, which has quite often evolved over time.

6. Free prior and informed consent (FPIC) legal provisions that require communities to be consulted before governments or companies can acquire their land or resources has been enacted in only seven states (Indicator 7: Does the law require the consent of Indigenous Peoples or communities before government or an outsider may acquire their land?). The main source of this limitation lies in persisting reluctance of governments to surrender unfarmed assets to their customary owners, to enable takings with no or minimum compensation for involuntary takings of their lands for oil, gas, mineral, timber, estate farming and other extractive purposes. Obligation to pay for resettlement or offer benefit shares from the intended enterprise is appearing in newer land laws, to discourage protest at involuntary losses. More positively, five of those seven countries extend FPIC as a right to be enjoyed by all land-dependent communities, not only Indigenous Peoples.

7. Recognition of communal land ownership is being fostered through other routes, such as natural resources (Indicators 8, 9, 10). Forest rights reform is a case in point. Twenty-one African states already provide enabling provisions for community owned and managed forests for protection and sustainable use, sometimes in states where recognition of communal lands is otherwise weak. Restitution of state forests to claimant communities has been a prominent action only in South Africa but is actively sought in five other states.

8. Conflict is inhibiting land rights reform in several countries. Armed conflict presently delays intended property reforms in Libya, Sahrawi, Somalia, and the Central African Republic, and impedes issue of regulations under enacted new land laws in Eritrea, South Sudan, and Mali. Military coups and violence have pushed land rights reform off the agenda in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad.

9. Only 2 of 53 African countries have laws specific to the rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Republic of Congo (2011) and Democratic Republic of the Congo (2022) have respectively enacted laws specific to Indigenous forest peoples in their countries, inclusive of commitment to respect their territories. At least ten other countries refer to Indigenous Peoples as marginalized communities deserving special concessions (e.g., Kenya, Guinea Bissau, South Africa, Algeria, Equatorial Guinea). Seven Sahelian countries consolidate the access and use rights of pastoralists in pastoral codes including designation of arid areas exclusive to them (Guinea, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Morocco, and Chad).

10. Overall, despite limitations and pushbacks, community land rights reformism is alive and well in Africa. Only 5 of 53 states have chosen to outlaw customary tenure-- one to capture lucrative oil lands (Libya), another to overcome seriously contested claims between those who fled civil war but returned and those who in the interim had occupied their lands (Rwanda), another because of the ethnically discriminatory practices customs had acquired (Mauritania), and two others for political reasons, but both of which have since found it necessary to replace community tenure with look-alike village regulated systems (Eritrea, Senegal). At this time, Benin, Ivory Coast, and Botswana have amendments to their land laws in place that suggest intention to extinguish customary tenure in favour of a single statutory regime. Nevertheless, most governments embrace land rights recognition of customary landholders, despite the difficulties. Their laws accept the logic of community-based tenure as the most tried and tested, and as modern in its localization, self-reliance, cost, as well as a just road to take further into the 21st century for more than 725 million people dependent on rural land.